The Evolution of Speed: A Journey through Hypercar History

Is there a better way to spark a debate? What exactly is a Hypercar, and how does it set itself apart from the Supercars we’re familiar with? Everyone has their own perspectives, and it's likely that many readers will either resonate with, challenge, or reflect on the ideas presented here. And that’s precisely the intention!

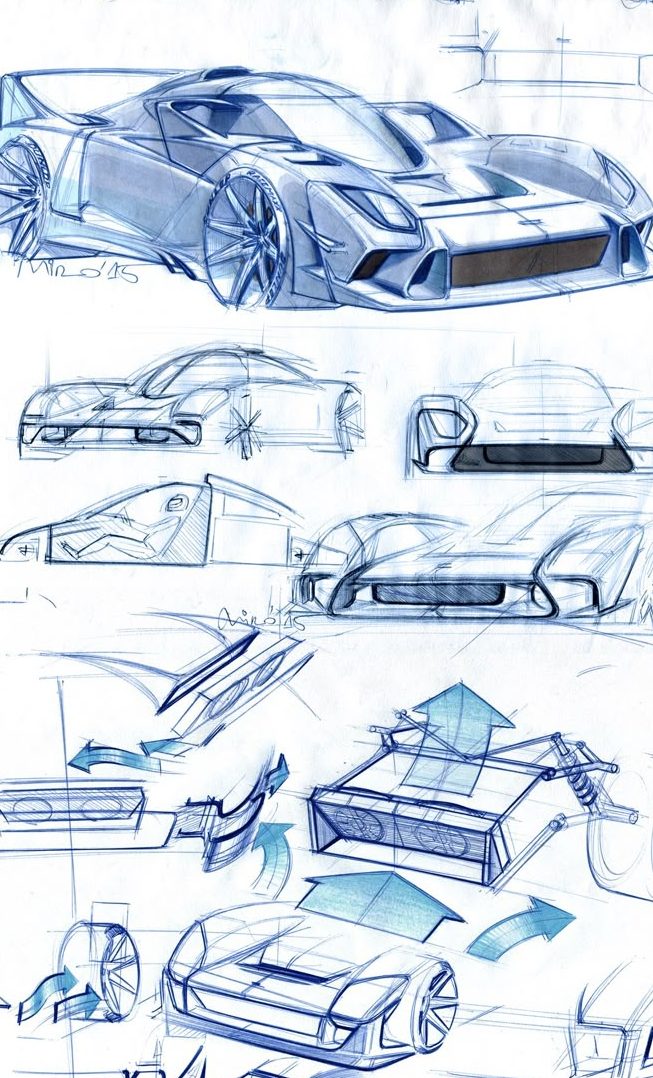

Are they the quickest? Are they the most powerful? Maybe they hold the title for the highest price or even the rarest? Could they be the most audaciously designed or visually stunning? Are they at the forefront of innovation, technology, and aerodynamics? Perhaps they can be seen as masterpieces? Do they evoke wonder and embody what a true Supercar should represent in the future, starting from today? We could spend days discussing what distinguishes a Hypercar from the rest, but honestly... all of these points could be considered valid. You might have your own opinions, but one thing is nearly universally accepted among car enthusiasts: a Hypercar epitomizes our vision of what a Supercar should be. It also serves as a reminder that, no matter how incredible the current Hypercar may be, it is only a matter of time before a designer creates an even more remarkable version that surpasses it.

For car makers such as Bugatti, Porsche, Ferrari and even McLaren the simplification of a Hypercar is something of an automotive sausage-fest. Who has the biggest?

For many leading manufacturers today, creating the ultimate Hypercar is often seen as a way to demonstrate their dominance in the industry. Interestingly, numerous modern Hypercars are produced and sold at a loss, with Bugatti being a prime example, as they lose money on most Hypercars sold. While this may not align with traditional business logic, it can actually be a more cost-effective strategy than many contemporary advertising methods. Volkswagen, Bugatti's parent company, invests millions in promoting their vehicles. When you consider the combined advertising budgets of Volkswagen's other brands—such as Audi, Bentley, Lamborghini, Porsche, Seat, and Skoda—the total expenditure is staggering. However, how many potential customers actually notice these ads on billboards, TV, or in magazines? In contrast, a significant number of potential Seat buyers are likely to be aware of the Bugatti Chiron. The prevailing belief among major manufacturers is that Volkswagen A.G. is behind the Bugatti Chiron, which is regarded as one of the most significant advancements in automotive technology in recent years. This association helps them stand out in a crowded market. For Volkswagen A.G., the respect and admiration that a future Seat or Skoda customer will have for the brand will be greatly enhanced.

Even Porsche and Aston Martin will occasionally venture into the Hypercar market (the 918 at $929,000/£729,000 or the Valkyrie at $3.2 million/£2.5 million). For these companies, as traditional Supercar builders, the creations of their own Hypercar’s show the world that they are the best at what they do. They have the expertise and prowess to create these amazing cars. Now how many more potential Supercar customers will look more attractively at a Porsche 718 Cayman at $57,000/£44,000 or an Aston Martin DB11 at $200,000//£150,000 knowing that the same factory built the Valkyrie and the 918?

This brings us to another key distinction between Hypercars and Supercars: their exclusivity. While most cars are produced in the hundreds of thousands or sometimes millions, Supercars typically have sales in the low thousands. In contrast, Hypercars are much rarer, often selling in the dozens or a few hundred, and frequently even fewer than that.

This shift has allowed more than just the big-name manufacturers with the expertise and facilities to manage large-scale operations to enter the Hypercar market. You don’t need to be Mrs. Porsche or Mr. Ferrari to create a Hypercar anymore. Smaller manufacturers with the skills to design and construct these incredible machines are emerging from modest workshops in lesser-known industrial areas. Additionally, affluent car collectors are increasingly valuing exclusivity alongside top speed, making this an exciting time for unique automotive creations.

The Evolution of Speed: A Journey through Hypercar History

Where did the Idea come from? Who created the first Hypercar concept?

Where did the first "extreme" cars originate? Supercars did not truly make their mark until the mid-1980s, and the term "Hypercar" has likely only been in popular use for about ten years. So, how did it all start?

To understand this, we should take a trip down memory lane to the early days of automotive innovation. The first vehicles that stand out are from the 1950s, particularly the Jaguar XKSS and the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR Uhlenhaut, which were both remarkable and extravagant for their time.

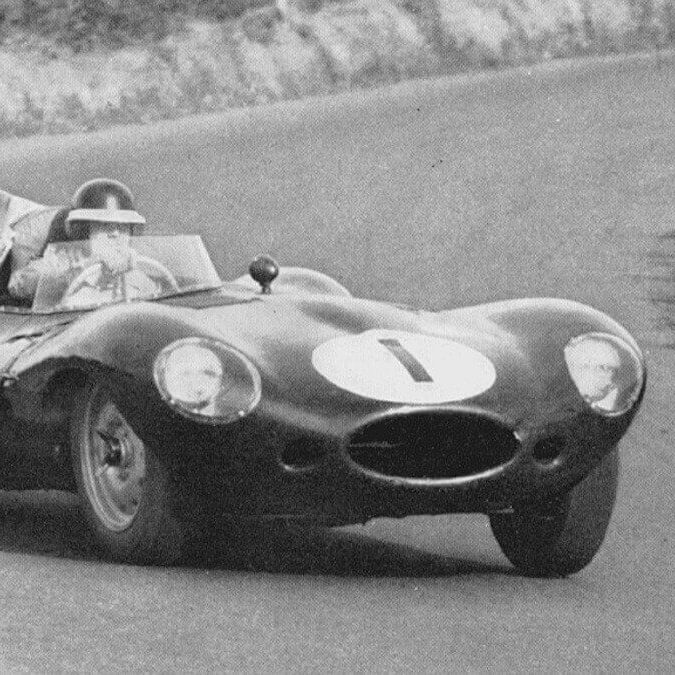

1954 Jaguar D-Type

Crafted to conquer the Le Mans 24 Hours, the Jaguar D-Type was engineered to be one of the most formidable race cars of its time. Produced from 1954 to 1957, this elegant racer shared its mechanical parts, including its straight-six engine, with its predecessor, the C-Type. However, the D-Type distinguished itself with a radically different design, featuring a streamlined, aviation-inspired body and pioneering monocoque construction. Under the guidance of Jaguar’s Technical Director and Chief Engineer, William Heynes, the D-Type's compact cross-section enhanced torsional rigidity, while its stunning elliptical form minimised drag.

The D-Type did not start its journey living up to all the hopes placed upon it. During its debut race in 1954, the car faced issues with fuel starvation, forcing it to make a pit stop to clear the fuel filters. Ultimately, the D-Types crossed the finish line over a lap behind their stronger competitors from Ferrari. Conditions quickly got better once the issues with the fuel filters were resolved. Just three weeks later, the D-Type triumphed in the Rheims 12-hour endurance race, achieving speeds over 12 mph faster on the straights compared to Ferrari. The progress continued throughout the year, and by 1955, the D-Type had been upgraded with a modified long-nose design and enhanced engines featuring larger valves. As a result, they began to outpace the Ferraris and were rapidly closing in on the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLRs.

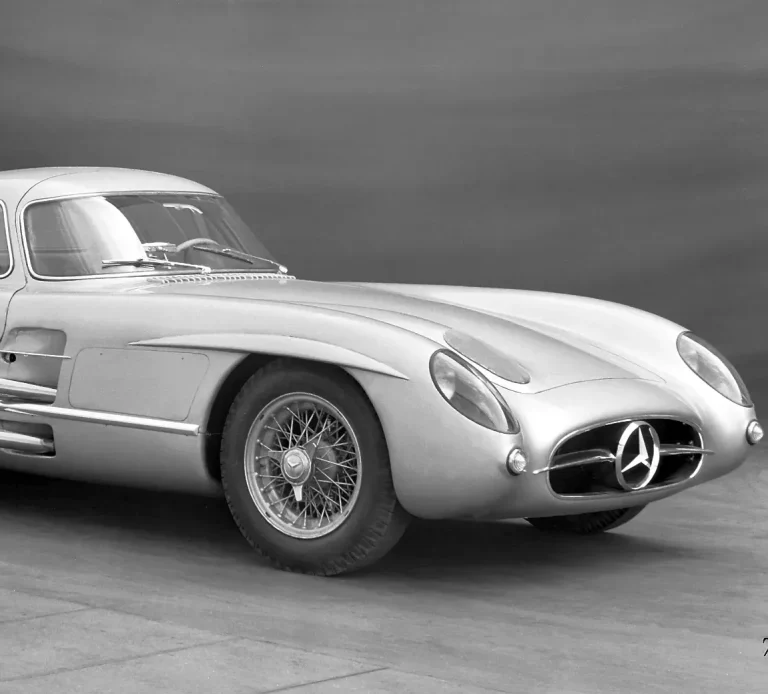

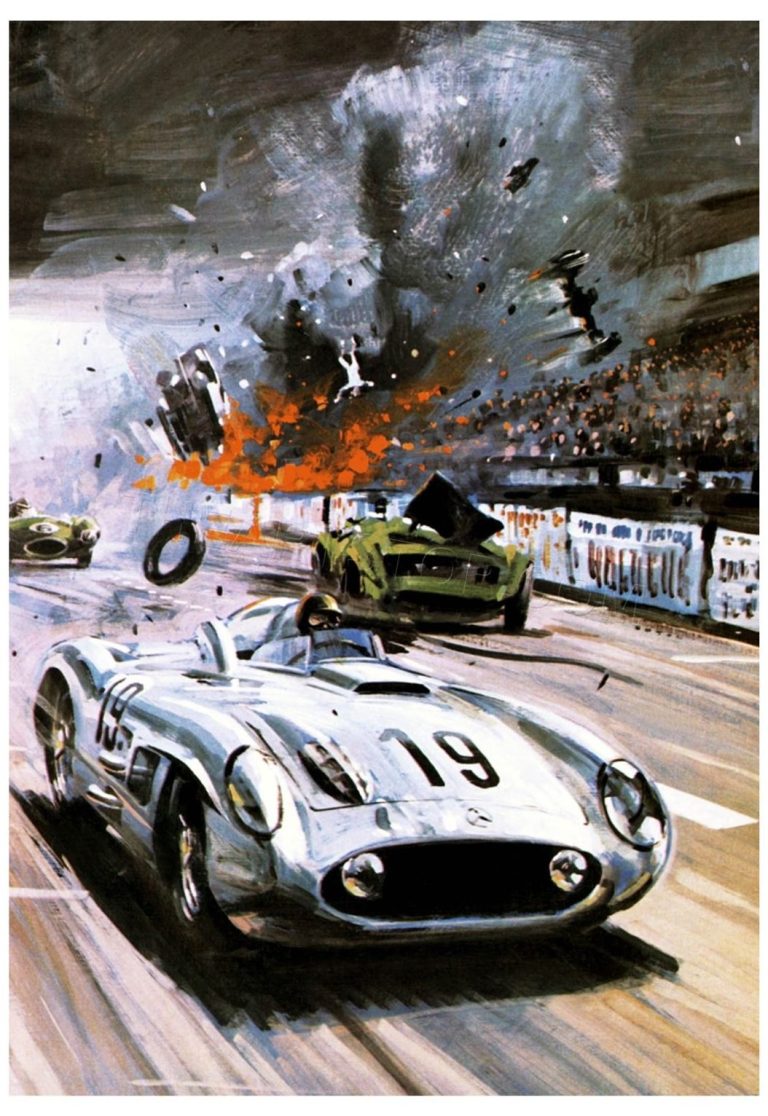

The 300 SLRs (Sport Leicht-Rennen/Sport Light-Racing) were two-seater sports racing cars based on the W196, which had triumphed in the Formula One Championship. Essentially, they were the W196 with an additional seat and two headlights added. The 300 SLRs quickly established their superiority, clinching victories in nearly every race they participated in. However, this dominance came to a halt on June 11, 1955, at the Circuit de la Sarthe in Le Mans, France.

Mike Hawthorn's D-Type cut in front of Lance Macklin's Austin-Healey right before the pits. In an attempt to avoid a collision, Macklin swerved and collided with the rear of Pierre Levegh's 300 SLR. This impact caused Macklin's Austin to become airborne and head towards the crowd. The car crashed into the dirt embankment beside the track, erupting in a massive fireball and ejected Macklin from the vehicle, resulting in his instant death on the track. The Austin continued to tumble, sending its burning engine and chassis into the audience. Tragically, eighty-three spectators lost their lives, and over 180 were injured, marking the 1955 Le Mans as the deadliest disaster in motorsport history.

Remarkably, the race continued despite the circumstances, with numerous cars still competing and passing by the hundreds of injured and dying spectators with each lap. An emergency meeting was convened among the directors of Mercedes-Benz via telephone in Stuttgart, West Germany. It was just before midnight when Mercedes team manager Alfred Neubauer received authorization to withdraw his team whilst the race continued. He chose to wait until 1:45 am, by which time many spectators had left, before he stepped onto the track to discreetly call his cars, which were in first and third place, into the pits. Their retirement was briefly announced over the public address system. By morning, the Mercedes trucks had been loaded and departed. Chief engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut approached the Jaguar pits to ask if the Jaguar team would also withdraw in respect for the crash victims, but Jaguar team manager "Lofty" England declined the request. Consequently, Mercedes-Benz withdrew from all motorsport activities and would not return to racing for another 34 years. This tragic event unexpectedly led to the development of our first extreme road cars and, more significantly, the creation of the Hypercar.

As Mercedes-Benz exited the world of motorsport, only two of their nine 300 SLR rolling chassis remained at the factory. At that time, the company's design chief, Rudolf Uhlenhaut, had transformed both chassis into an SLR/SL Hybrid. This modification involved installing a large muffler in the rear to reduce the noise of the loud exhausts, adding a roof, slightly widening the chassis, and incorporating the iconic "gull-wing" doors of the SLR. These doors were designed to accommodate the high sill beams of the SLR, a feature that would unexpectedly influence the design of many future supercars and Hypercars. Uhlenhaut had originally planned to enter both vehicles in the Mexican Carrera Panamericana race; however, with Mercedes' withdrawal from motorsport, the cars were left unused.

Determined not to let such exquisite examples of German engineering go to waste, Uhlenhaut opted to use one of the cars for his personal transportation. After fitting road tires, Mercedes-Benz unexpectedly found themselves in possession of the fastest road car in the world. The 300 SLR boasted a top speed nearing 180 mph (290 km/h). According to legend, on one occasion, when he was late for a meeting, Uhlenhaut accelerated the SLR on the German autobahn from Munich to Stuttgart, completing the 137-mile (220 km) journey in an impressive one hour. Even today, that trip would take nearly two and a half times longer. Consequently, the 300 SLR coupe became famously known as the 300 SLR Uhlenhaut.

The Uhlenhaut Coupé has been preserved by Mercedes and is displayed at its corporate museum in Sindelfingen near Stuttgart. Its sibling is preserved in one of Mercedes' eleven car vaults.

While Mercedes chose to exit the racing scene, Jaguar decided to persist with the D-Type. Lacking significant competition from the 300 SLRs, privately funded teams, utilising the D-Type, excelled in motor racing, achieving victory at Le Mans in 1955, 1956, and 1957. However, in 1956, Jaguar's own factory team was underperforming, leading them to withdraw from racing as well. At Jaguar's Brown Lane Factory, there were 25 partially completed D-Types remaining, and in an effort to recover some of the financial losses incurred from racing, they resolved to convert these vehicles into road-legal cars that could also participate in private sports car events.

The prominent rear fins were removed, and a passenger seat along with a side door was installed. A full-width windscreen, framed in chrome, was added, along with a folding hood for inclement weather. Additionally, higher-mounted rear lights and bumpers were affixed, and the rear of the vehicle was adorned with its new designation: the XKSS. The drivetrain and chassis were retained, featuring a fuel-injected, bored straight-eight engine, enhanced to 2,981.70 cc and producing 310 bhp. Inadvertently, Jaguar had also created one of the fastest road cars in the world.

The unveiling of the XKSS by Jaguar and the 300 SLR Uhlenhaut by Mercedes provided the first insight into the potential of high-performance vehicles on public roads. It would take many years for such cars to become commonplace, and while only a select few ever made it to the streets, both manufacturers and the global audience were introduced to a ground-breaking concept.

Jaguar successfully sold sixteen units of the new XKSS, primarily to customers in the United States. However, on the night of February 12, 1957, a fire erupted at the Browns Lane factory, resulting in the destruction of the remaining nine vehicles.

Nearly ten years after the introduction of Uhlenhaut’s 300 SLR and the XKSS, other manufacturers began to explore the concept of transforming race cars into road-legal vehicles. A notable example of this trend was Alfa Romeo, which saw former Bertone designer Franco Scalione present his designs for what would ultimately become the Alfa Romeo 33 Stradale (with "Stradale" translating to "road-going" in Italian).

The Stradale was developed from the Alfa Romeo Tipo 33 racing car variants and made its official debut on August 31, 1967, just before the Italian Formula 1 Grand Prix at Monza. Measuring under four meters in length and standing only 39 inches tall, the vehicle featured compact 13-inch wheels. Despite its small stature, it housed a mid-mounted 2.0-litre V8 engine derived from the Tipo 33, capable of reaching a redline of 10,000 rpm and producing 230 bhp at 8,800 rpm. However, this figure was an average, as no two Stradale’s were identical due to their hand-built nature. The 33 Stradale also utilised the 6-speed transmission from the Tipo, and with a weight of just 700 kg (1,543 lb), it delivered exhilarating performance.